In the waning days of the Mayan empire, one man will stop at nothing to save his family.

Jaguar Paw leads a simple hunter-gatherer life among his fellow Mayan villagers, providing for his pregnant wife, Seven and toddler son Turtles Run. While hunting with his father and some friends, Jaguar Paw becomes alarmed when the group stumbles upon a group of impoverished villagers seeking “a new beginning” as they pass through the jungle. However, Jaguar Paw’s father, Flint Sky, encourages his son to not let the “sickness” of fear affect him.

The next morning, Jaguar Paw’s village is ransacked by a group of vicious warriors, led by the fierce Zero Wolf and the sadistic Middle Eye. Jaguar Paw evades his captors at first, hiding his wife and son in an empty well before eventually being knocked unconscious. In the ensuing fracas, Flint Sky is killed in front of his son, while Jaguar Paw and his fellow male villagers are tied up and forced to march to the city. The women and children are either killed, violated or left to starve.

En route to the great Mayan city, the captors view numerous disturbing sights, including deforested crops, destitute, plague-infested populations and greedy merchants. Upon their arrival to the city, Jaguar Paw & Co. discover that they are to be sacrificed to the gods, but after a sudden solar eclipse, their fate is suspended. Eventually, Jaguar Paw escapes and leads his captors on a pulse-pounding journey through the jungle as he attempts to go back home and save his family.

Apocalypto is an unusual film in more ways than one. It came out in 2006 — a perfect time for me. At the time, I was a 13-year-old in Virginia who was first seriously considering a career in the movies, and this action-adventure film was one of the first that really opened my eyes to what the power of film was and what it could do. It also helped that it was a foreign language film; to a kid growing up in a largely homogenous small city, it was a window into a whole new world.

Part 1: Background and Context

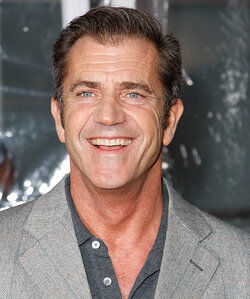

Apocalypto was actor/director Mel Gibson’s first movie after his controversial, record-breaking religious epic The Passion of the Christ in 2004 — but apart from the “foreign language film” branding, Apocalypto was a much different movie. The Passion was an independent film largely financed by Gibson’s own Icon Productions; meanwhile, Apocalypto was a $40 million production released by Disney subsidiary Touchstone Pictures.

Although the violence, torture and alleged anti-Semitism in The Passion of the Christ drew significant detractors, others admired Gibson’s film purely as a daring artistic endeavor. The Passion smashed nearly every box office record for an R-rated film or a religious film, grossed $625 million worldwide and received three Academy Award nominations. It received acclaim from both Protestants and Gibson’s fellow Catholics, opened up a larger landscape for realistic Biblical epics and gave Gibson renewed clout after nearly a decade away from the director’s chair.

So how do you follow up that?

Any foreign language film is a gamble for American audiences. Perhaps no one other than Gibson would be able to pull off back-to-back epic films featuring unknown actors speaking dead languages.

“I think hearing a different language allows the audience to completely suspend their own reality and get drawn into the world of the film,” the director stated. “And more importantly, this also puts the emphasis on the cinematic visuals, which are a kind of universal language of the heart.”

Filmed mostly in the Yucatán peninsula of Mexico and featuring a completely unknown cast of Native American and Hispanic actors, Apocalypto was non-traditional in a variety of ways. Nonetheless, it’s a deceptively simple story — an action/adventure flick about a guy who gets kidnapped, eludes his fate as a potential human sacrifice, and sprints back to the forest to search for his family. It’s a cat-and-mouse chase film with no sci-fi effects, explosions or cliches.

Part 2: Filmmaking Influences & Story Development

The roots of Apocalypto began to blossom largely thanks to Gibson’s unlikely partnership with Farhad Safinia, an Englishman who worked on post-production of The Passion. The two men immediately bonded over their mutual love of storytelling, and both Gibson and Safinia said that they wanted to make a high-quality action film with no CGI or complicated effects.

“We wanted to update the chase genre by not updating it with technology or machinery, but stripping it down to its most intense form: which is a man running for his life, and at the same time, getting back to something that matters to him,” Safinia said.

In addition to his and Safinia’s desire to make an old-school chase movie, Gibson also said that he wanted the film to explore pre-Columbian civilizations and why they fell. Just like The Passion, Apocalypto features no opening credits and includes a singular quote, in this case from Will Durant: “A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.”

Gibson and Safinia considered doing a film about the Aztecs, but ultimately opted for the Mayans. “You can choose a civilization that is bloodthirsty, or you can show the Maya civilization that was so sophisticated — with an immense knowledge of medicine, science, archaeology and engineering — but also be able to illuminate the brutal undercurrent and ritual savagery that they practiced. It was a far more interesting world to explore why and what happened to them,” remarked Safinia.

Gibson and Safinia used several Mayan holy books, including the Popul Vuh, to give them historical and creative inspiration for the screenwriting process. They also examined accounts of Spanish conquistadors, who described the Maya in their journals.

The two men did a wide variety of location scouting during pre-production. They initially looked at jungles in Guatemala and Costa Rica before switching course and choosing to film in the Yucatán Peninsula. Most filming was conducted in the state of Veracruz, specifically the areas surrounding San Andrés Tuxtla, Paso de Ovejas and Catemaco.

While Gibson’s vision of the pre-Columbian Americas is undeniably intriguing (helped by some stunning cinematography), this is still an adrenaline-pumping action film at its heart. The real influence behind Apocalypto‘s brilliance might actually be George Miller — the acclaimed Australian filmmaker who first brought Gibson to prominence as an actor with the Mad Max trilogy. Gibson’s directorial style is very similar to Miller’s, with lots of on-screen violence, minimal dialogue and gorgeous images to boot. And that’s not the only connection: Apocalypto director of photography Dean Semler, one of the most acclaimed cinematographers in the industry, worked with Gibson, a fellow Aussie, on Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior in 1981. The way Gibson cranks up the suspense and violence in the film really feels like a throwback to the ’80s heyday of Miller.

As strange as it may sound, Apocalypto also feels like a culmination of many of Gibson’s career highlights. A suspenseful chase film with minimal dialogue (Mad Max). A historical, albeit somewhat inaccurate, portrayal of a real moment in history (Braveheart). And, of course, a film entirely in a dead language (The Passion).

While the brutality of human sacrifice is a harrowing and visually stimulating spectacle, the subsequent chase sequences are truly epic and need to be seen to be believed. But even the drawn-out prelude to the sacrifice scene — where Jaguar Paw and his friends see the decay and disrepair of the once-great Mayan city — is exquisitely shot by Semler and builds the tension up while once again using dialogue sparingly.

Part 3: Non-Actors Acting

The acting is excellent, especially considering that they’re all completely unknown. Lead actor Rudy Youngblood, a Native American from Belton, Texas, has the physical build of an action star in addition to a great mix of raw charisma and vulnerability. Dalia Hernandez — in her film debut as Jaguar Paw’s wife, Seven — has an innocent look to her that makes her experiences in the film all the more harrowing and intense. Gibson explicitly said that he had to consider character archetypes and facial structures when he auditioned these inexperienced actors — as opposed to simply talent alone — and he thought that Youngblood had a convincingly heroic look to him. Youngblood was a high school track and field star who also had experience in boxing and traditional Native dance prior to becoming an actor. He performed all of his own stunts in the film.

Jonathan Brewer and Morris Birdyellowhead are two other actors who shine in brief but pivotal roles: Birdyellowhead as Jaguar Paw’s father, Flint Sky, and Brewer as Blunted, a friend of Jaguar Paw’s who’s frequently the subject of locker-room jokes due to impotency issues with his wife. While Blunted makes for good comic relief early on in the film, he’s also a loyal friend who is there for Jaguar Paw until the very end. Meanwhile, Flint Sky’s wisdom provides a guiding light for his son that permeates throughout the film. Both Brewer and Birdyellowhead are First Nations actors from Alberta, Canada.

Apocalypto has a murderer’s row of intimidating villains, highlighted by Raoul Trujillo and Gerardo Taracena, who play lead villain Zero Wolf and his second-in-command, Middle Eye, respectively. These two actors really shine, using subtle expressions and non-verbal cues to send menacing messages, particularly in the latter half of the film when their fellow warriors start biting the dust.

Based on how consistently good the acting is in Apocalypto, it’s hard to tell who’s relatively experienced and who isn’t, but Trujillo and Taracena were actually some of the more veteran actors on set. Taracena had a brief role in the 2005 Denzel Washington action flick Man on Fire, while Trujillo, a Native American from Taos, New Mexico, was an experienced actor, painter and traditional dancer before being cast in Apocalypto. A handful of other Mexican character actors also rounded out the cast, including Mayra Serbulo, Israel Contreras, Ricardo Diaz Mendoza, Fernando Hernandez, Carlos Ramos and Marco Antonio Argueta.

These actors were put through the ringer, filming in dense Mexican jungles and also learning a new language from scratch for the film. As mentioned before, Apocalypto‘s dialogue is entirely in the Yucatec Mayan language, accompanied by English subtitles.

Part 4: Historical and Academic Influences

“Maya civilization in the Central Area reached its full glory in the early eighth century, but it must have contained the seeds of its own destruction,” says archaeologist Michael Coe. “In the century and a half that followed, all its magnificent cities had fallen into decline and ultimately suffered abandonment. This was surely one of the most profound social and demographic catastrophes of all human history.”

True enough, we still don’t actually know exactly what happened to the Mayans before the Spanish conquest, and there are many theories out there.

At its height, the Mayans occupied most of southeastern Mexico in addition to Guatemala, Belize, and parts of El Salvador and Honduras. The Mayan civilization itself can be broken down into pre-Classic, Classic and post-Classic periods. The post-Classic Maya period (roughly 950-1530 AD) was basically the beginning of the end. Various cities were conquered by Europeans or by neighboring tribes. Some once-great Mayan cities were abandoned, and yet others continued to thrive only a few miles away. While Europeans made first contact with the Maya in 1511, the last Mayan city, Nojpetén, didn’t fall until 1697. There was even a tribe, the Lacandón people, who vanished into the jungle and lived completely uncontacted and unmolested until the 1920s!

Many experts believe that it was environmental problems — including drought, deforestation, or famine — that did these people in. Or maybe it was all of the above. But Apocalypto also hints at many other factors, not the least of which were widespread slavery, vicious human sacrifice, power-hungry leaders, vicious tribal infighting and excessive consumerism.

According to Gibson, the themes of Apocalypto aren’t necessarily specific to the decline of the Mayan culture and include relevant comparisons to modern day countries and peoples.

“It was important for me to make that parallel because you see these cycles repeating themselves over and over again,” Gibson said. “People think that modern man is so enlightened, but we’re susceptible to the same forces – and we are also capable of the same heroism and transcendence.”

Gibson and Safinia enlisted the help of two consultants for Apocalypto‘s production: Dr. Richard Hansen, an anthropology professor and an expert on the Maya, and Hilario Chi Canul, a young linguistics professor at the University of Quintana Roo who translated the script into Yucatec Mayan. Both men proved invaluable on the production.

In addition to bringing in Semler as cinematographer, Gibson also looked to production designer Tom Sanders (a former Braveheart colleague) to recreate the awe-inspiring Mayan city for the film, using very little CGI or visual effects to come up with the finished product. The final human sacrifice scene featured over 700 extras.

Oscar-nominated makeup artist Aldo Signoretti supervised the extremely detailed jewelry, makeup and tattoos that the Mayans wore in the film. Propmaster Simon Atherton, another Braveheart veteran, designed all of the ancient weapons used onscreen.

Part 5: Reception

Apocalypto was a critical and commercial success when it was released in December 2006, grossing over $120 million worldwide against a production budget of $40 million. Many critics praised the film, while some disliked it for historical inaccuracies and for its graphic violence.

Unfortunately, Apocalypto got overlooked at many awards shows for completely different reasons. The film was released only a few months after Gibson’s now-infamous DUI arrest in Malibu, where he drunkenly made anti-Semitic comments to the arresting officer.

“Say what you will about Gibson – about his problem with booze or his problem with Jews – he is a serious filmmaker,” remarked A.O. Scott of the New York Times. Ty Burr of The Boston Globe quipped: “Gibson may be a lunatic, but he’s our lunatic, and while I wouldn’t wish him behind the wheel of a car after happy hour or at a B’nai Brith function anytime soon, behind a camera is another matter.”

Gibson’s film also gained several passionate defenders among fellow members of the Hollywood community. “I think it’s a masterpiece,” remarked Quentin Tarantino. “I think it was the best artistic film of that year.”

“I was totally caught off guard,” said Oscar-winning actor Edward James Olmos. “It’s arguably the best movie I’ve seen in years. I was blown away.”

“Many pictures today don’t go into troubling areas like this: the importance of violence in the perpetuation of civilization,” said Martin Scorsese. “I admire Apocalypto for its frankness, but also for the power and artistry of the filmmaking.”

In addition to gaining critical acclaim from general American audiences, the film was largely well-received by Mexicans and Native Americans. Both Rudy Youngblood and Morris Birdyellowhead won acting awards from the First Americans in the Arts (FAITA) organization. Gibson also screened the film to audiences at the Latino Business Association in Los Angeles and to various Native American organizations in Oklahoma. While accepting the Chairman’s Visionary Award for the Latino Business Association, Gibson stated that his goal for the film was to dispel the myth that “history began with Europeans.” In a poll, 80% of Mexicans labeled Apocalypto as either “good” or “very good.”

To be sure, Apocalypto had its fair share of detractors, many of whom were dissatisfied about the representation of the Maya. Mexican journalist Juan Pardinas remarked, “This historical interpretation bears some resemblances with reality, but Mel Gibson’s characters are more similar to the Mayas of the Bonampak murals than the ones that appear in the Mexican school textbooks.”

Other commentators stated that the savagery present in Apocalypto — specifically the human sacrifice scenes — was more representative of the Aztecs than the Maya.

“The first researchers tried to make a distinction between the ‘peaceful’ Maya and the ‘brutal’ Aztec cultures of central Mexico,” said researcher David Stuart. “They even tried to say human sacrifice was rare among the Maya.”

Dr Hansen responded by stating, “We know warfare was going on…there was tremendous Aztec influence by this time. The Aztecs were clearly ruthless in their conquest and pursuit of sacrificial victims, a practice that spilled over into some of the Maya areas.”

On the DVD commentary, Gibson and Safinia stated that the depiction of latter-day Mayan culture was relatively consistent with what was going on elsewhere in 15th-century Central America, where culture-borrowing was not uncommon as various civilizations began to crumble and — in the case of the Maya — vanish unexpectedly. Therefore, the argument becomes that Mayan and Aztec cultures could have blended together more than anticipated in the decades leading up to European contact.

It’s also worth mentioning that the ancient Mayans themselves didn’t view themselves as one unified people group. Much like the ancient Greeks, the Mayans were primarily clustered around city-states and were never one cohesive empire like the Aztecs or the Romans.

This would explain why the peaceful forest-dwellers like Jaguar Paw are completely unprepared for the vicious neighboring tribes to invade, kill and kidnap early on in the movie. While many Mayan experts have claimed that nobility were far more likely to be sacrifice victims than commoners, the film implies that the drought and deforestation has become so severe that the Mayan rulers are willing to basically sacrifice thousands — regardless of socioeconomic status — in order to appease the gods. During the human sacrifice scene, the high priest makes references to the ongoing drought and seeks to appease the god Kukulkan, a notable Post-Classic Mayan deity.

The architecture of the Mayan temple is more or less accurate, but it’s blended from several different eras of Mayan civilization, not just the Post-Classic Maya period in which the film takes place.

“We wanted to set up the Mayan world, but we were not trying to do a documentary,” said production designer Tom Sanders. “Visually, we wanted to go for what would have the most impact…our job is to do a beautiful movie.”

“There was nothing in the Post-Classic period that would match the size and majesty of that pyramid in the film,” admitted Hansen. “But Mel was trying to depict opulence, wealth and consumption of resources.”

To that end, audiences can see quite a bit of the forces that contributed to the Mayans’ collapse. In the lengthy sequences where Jaguar Paw and his friends are being taken to the Mayan city, we can see the stark contrast between the high-bred, extravagant nobility versus the sick, starving people begging in the street. The Mayan slave trade is depicted, with many of them creating lime stucco cement, which was used to paint the temples and wreaked havoc on the local ecosystem.

Conclusion

In a rare hour-long interview in 2016 while promoting his film Hacksaw Ridge, Gibson referred to his basic philosophy of filmmaking, summed up by what he calls “the three Es.” If you can entertain and only entertain, that’s totally valid. But if you entertain and you educate, that’s better. And if you can entertain, educate and elevate, then you’ve done your job.

Regardless of historical accuracy, Apocalypto stands alone as both a bloody, heart-pounding action film and as a unique artistic achievement. I still find myself mesmerized by it whenever I rewatch it. Check it out.

- Directed by Mel Gibson

- Produced by Mel Gibson, Farhad Safinia and Bruce Davey

- Written by Mel Gibson & Farhad Safinia

- Executive Producers — Ned Dowd and Vicki Christianson

- Director of Photography — Dean Semler

- Music by James Horner

- Editor — John Wright

- Casting Director — Carla Hool

- Production Designer — Tom Sanders

- Costume Designer — Mayes C. Rubeo

- Starring Rudy Youngblood, Dalia Hernández, Jonathan Brewer, Morris Birdyellowhead, Carlos Emilio Baez, Raoul Trujillo, Gerardo Taracena, Ricardo Diaz Mendoza, Rodolfo Palacios, Amilcar Ramirez, Israel Conteras, Bernardo Ruíz, Richard Can, Carlos Ramos, Israel Ríos, Ariel Galván, Maria Isabel Diaz, Mayra Serbulo, Iazua Larios, Ammel Rodrigo Mendoza, Marco Antonio Argueta, Fernando Hernandez, Maria Isidra Hoil

- Rated R for sequences of graphic violence and disturbing images.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM

“Any Gibson-haters hoping to see the heart ripped out of his success may well find themselves disappointed by Apocalypto‘s relative merits.”

–Anton Bitel, Film4

“Outrageously entertaining and thrillingly kinetic. While the ancient dialects and weighty quotations suggest an arthouse epic, Apocalypto is basically a really good period popcorn flick.”

–Paul Arendt, BBC

“Apocalypto isn’t simply an effective movie, but an immensely powerful one.”

–David Keyes, Cinemaphile.org

“Mel Gibson is always good for a surprise, and his latest is that Apocalypto is a remarkable film.”

–Todd McCarthy, Variety

“A stunning achievement…one of the most visceral, primal and thoroughly engrossing films I have seen in a long time.”

–Matthew Lucas, The Davidson County Dispatch

“Gibson’s passionate spectacle of human destruction and doom packs a terrific visceral punch.”

–Jeff Meyers, Metro Times

“No matter what your interest is in the film — entertainment or information — Apocalypto delivers the goods, and then some.”

–Todd Gilchrist, IGN Movies

“Apocalypto turns out to be not a case of Montezuma’s revenge but of Gibson’s. It’s something entirely unexpected — a sinewy, taut poem of action.”

–Stephen Hunter, The Washington Post

“Offers non-stop excitement…an electrifying epic in every sense of the word.”

—Pete Hammond, Maxim

“Brutal, compelling and utterly convincing, Apocalypto is an adventure that stuns, overwhelms, and above all else, entertains.”

–Linda Cook, Quad City Times

TRIVIA

- A humorous reference to Midnight Cowboy is included in Apocalypto. When Zero Wolf is walking his captives through the forest on the way to the Mayan city, a tree suddenly collapses and nearly crushes several prisoners. Annoyed, Zero Wolf yells, “I am walking here!” — just like Dustin Hoffman’s character famously did in Midnight Cowboy.

- When filming the exhilarating waterfall scene in the latter half of the film, a cow that was trying to cross upstream got caught in the current and went over the falls. Gibson and the crew thought that the creature was done for, but amazingly, it picked itself up at the bottom of the waterfall and walked away only slightly dazed.

- For the waterfall jump scene, Rudy Youngblood jumped from a harness from the top of a 15-story building in Veracruz, which was then digitally super-imposed over the actual waterfall in post-production. Gibson gave Youngblood a ribbing about doing the stunt, which prompted Youngblood and the stunt crew to goad Gibson into making a leap himself.

- The filmmakers had to take extra care to protect the digital cameras from the unpredictable rainforest climate. They were covered with space blankets to reflect the extreme heat, and temperatures were closely monitored thanks to special thermometers attached to the cameras.

- Principal photography was completed in July 2006. The release of the film was delayed until December due to hurricanes and flooding in Mexico. Cast and crew helped with flood relief, as over a million Mexican citizens were displaced due to the disaster.

- Some critics took issue with the solar eclipse, which stops the human sacrifice scene halfway through the film. Many of the Mayan people are depicted as frightened of the eclipse, but critics argued that this wouldn’t have happened, as the Mayans were highly-skilled astronomers. On the DVD commentary, both Gibson and Safinia stated that their intent was to show how the Mayan aristocrats would use astronomical events to control the common people.

- The film is dedicated to the memory of Abel Woolrich, who plays a brief role and who passed away unexpectedly before the film was released.

- Gibson turned down the lead role in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center in order to make Apocalypto. The role eventually went to Nicolas Cage.

- The silhouetted character on the poster is actually not Jaguar Paw, but one of the antagonists, Middle Eye (played by Gerardo Taracena).

- Gibson originally wanted to shoot on location in Costa Rica or Guatemala, but the jungles there were too thick. He did, however, make some notable philanthropic efforts in that part of Central America, donating $500,000 to Richard Hansen’s conservation group, the Mirador Basin Project. Gibson later bought a rural estate on the Costa Rican coast.

- When the prisoners pass through a construction site on the way to the Mayan city, they see numerous slaves covered in white powder. The white powder being mined and processed is lime, which was used for building and covering the Mayan pyramids. If inhaled, it causes irritation and inflammation; as a result, the workers had brief life expectations, as can be seen by a slave who coughs up blood on camera. Raw lime is caustic enough that it was even used in ancient cultures to accelerate the decomposition of corpses.

- Final body count: 114.

- Early on in the film, Jaguar Paw and his fellow villagers listen to an ancient story told by an elderly shaman about humans abusing natural resources. The actor playing the storyteller, Espiridion Acosta Cache, was actually a tribal elder himself. Safinia said that the story told in the film was a modern-day approximation of a similar traditional story translated into Mayan.

- Included in 1,001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, edited by Steven Schneider.

- Gibson made a brief, tongue-in-cheek appearance in the film’s trailer. He showed up in a couple of frames with a full beard, smoking a cigar.